Consider the impact and importance of 'The Prince' in political history, as notable leaders such as Napoleon Bonaparte, Benito Mussolini, John F. Kennedy, and Richard Nixon engaged with its strategies. Like most ancient books, it is not easy to read, but we have a detailed summary on the Headway app.

You may be familiar with 'The Prince,' a key work of world literature authored by the famous 16th-century political thinker Niccolò Machiavelli. Discussions surrounding Machiavelli's ideas continue; some consider him a cynic, while others consider him a realist.

Here's what you'll learn in this article:

1. Why Machiavelli was a revolutionary thinker

2. The main principles of 'The Prince,' include:

Why it's safer to be feared than loved

How a ruler should balance image and action

The role of military strength in leadership

3. How Machiavellian tactics are used in modern politics and business

4. Where to read or listen to a quick summary of 'The Prince'

Period in history: Crisis of the Florentine Republic

The humanist movement flourished in Italy during the 15th century, with Florence as a major center. Lorenzo de' Medici played a significant role in promoting humanism, infused with Epicurean and pagan influences. At that time, Italy was a picture of complete internal discord. The entire peninsula was breaking up into separate states, and all of them looked at each other not as parts of a single whole that had accidentally fallen apart but as enemies.

There was a complete absence of a shared national spirit throughout Italy, and even the word "Italy," which had not disappeared from the popular language, did not represent any specific concept. The ancient center — Rome — lost its primacy, while several other cities of no less importance on the Apennine Peninsula existed. The Florentine Republic became Western Europe's most significant financial center, and the Medici Bank became the most prominent European bank.

Revolutionary thinker of the European Renaissance

Niccolò Machiavelli was an Italian writer, political philosopher, and theorist of the late Italian Renaissance. The merits of Machiavelli in the history of political thought are that he:

Separated politics from morality and religion for the first time in history, making it an autonomous, independent discipline

Rejected scholasticism, replacing it with rationalism and realism

Laid the foundations of political science

Spoke out against feudal fragmentation for the creation of a centralized Italy

Introduced the concepts of "state" and "republic" in their modern understanding into the political vocabulary

Demonstrated democracy by placing the common good above all else

Interpreting 'The Prince'

In the political treatise 'The Prince' (Il Principe, 1513), Machiavelli reflects on the nature of power and its practical application and provides specific guidance for the ideal ruler. The motto of this treatise is "The end justifies the means." This term does not mean the utopian ideal of a perfect head of state but a collective image of a far-sighted and power-hungry ruler who understands political intrigues and knows how to stay in power.

Machiavelli's virtue

The Florentine became the first political strategist to meticulously pay attention to building the ruler's image. For clarity, Niccolò Machiavelli's views differ somewhat from the common interpretation of Machiavellism. This term generally refers to a ruler's blend of cunning, cruelty, and manipulativeness — traits often linked to psychopathy. However, Machiavelli did not express such extreme views regarding the qualities of those in power.

Interestingly, Machiavelli argued that political leaders often pursued their goals without regard for ethical constraints during the Middle Ages. His philosophical perspective is based on the interaction between two types of power: natural and irrational power, which relies on the brute force of the state, and organizing and ordering power, which elevates society above mere biological instincts.

What is the image of a true leader?

"He who wishes to be obeyed must know how to command." ― Niccolò Machiavelli, 'The Prince'

In 'The Prince,' Niccolò Machiavelli speaks of a "new prince" as a ruler who gains power not through hereditary rule but through his efforts, cunning, military strength, or the people's support.

Machiavelli uses the portrait of Cesare Borgia, the son of Pope Alexander VI, as an example of a successful ruler. Modern literary critics define the genre of this work as a dystopia since it is here that the most tragic and anti-humane ideas of the 16th century developed.

During the power struggle, Machiavelli depicts the image of a ruler who neglects the law of morality and religion. The ruler's actions primarily depend on how they strengthen the state's power and their methods to achieve it. Machiavelli gives the ruler his native indulgence, not a violation of moral commandments.

Safer to be feared than loved

"Since love and fear can hardly exist together, if we must choose between them, it is far safer to be feared than loved." ― Niccolo Machiavelli, 'The Prince'

Machiavelli states that the best approach is to inspire love and fear, but a ruler cannot achieve them simultaneously. One should prefer fear because love is weak and changeable due to its corrupt nature, and fear of punishment is always effective.

However, Machiavelli's citizenship sometimes takes on fanatical forms; he is ready to justify sacrifices for the common good, the state, and the fatherland. At the same time, Machiavelli feels the distance between the absolute and relative ideals of man and the statesman. The chapters of 'The Prince' often begin with the words: "It would be commendable to be good and honest..." but he immediately moves on to opposite arguments.

Machiavelli is sure that the one who relies less on the mercy of fate rules longer, as it is complicated for rulers who come to power quickly to hold on to it. Therefore, the one who goes through numerous trials possesses everything necessary for a long reign.

Need to maneuver

"Therefore, it is necessary to be a fox to discover the snares and a lion to terrify the wolves." ― Niccolo Machiavelli, 'The Prince'

Niccolo Machiavelli justifies the duplicity of the statesman, who sometimes has to promise a lot and then evade fulfilling what he promised; he also justifies the abandonment of previous beliefs if the interests of state integrity require it. According to 'The Prince,' one of the essential arts of governance is the ability to maneuver between the nobility and the ordinary people, constantly considering the mutual disunity and hatred of the classes.

Additionally, Machiavelli believed that politicians should operate within the realities of the world, using any means necessary to achieve their goals. He argued that people are often selfish, greedy, and cruel, which is why the existence of a state is essential to curb these negative traits. He prioritized secular power and sharply criticized the clergy, advocating for eliminating the nobility.

His ideal system of government was a strong, rigidly centralized republic led by representatives of the people, particularly the young bourgeoisie, along with an elected head of state. Given the inherent flaws in human nature, this leader should be shrewd and cunning.

The ruler must know military affairs perfectly

"A prince must not have any other object nor any other thought but war, its institutions, and its discipline because that is the only art befitting one who commands." ― Niccolò Machiavelli, 'The Prince'

There is only one guarantee of intense power, which must be laid at its very foundation — a strong army. This is natural because the Machiavellian statesman is a person who speaks to the world around him in the language of force. After all, only a person endowed with such a character and the corresponding state can survive a cruel reality.

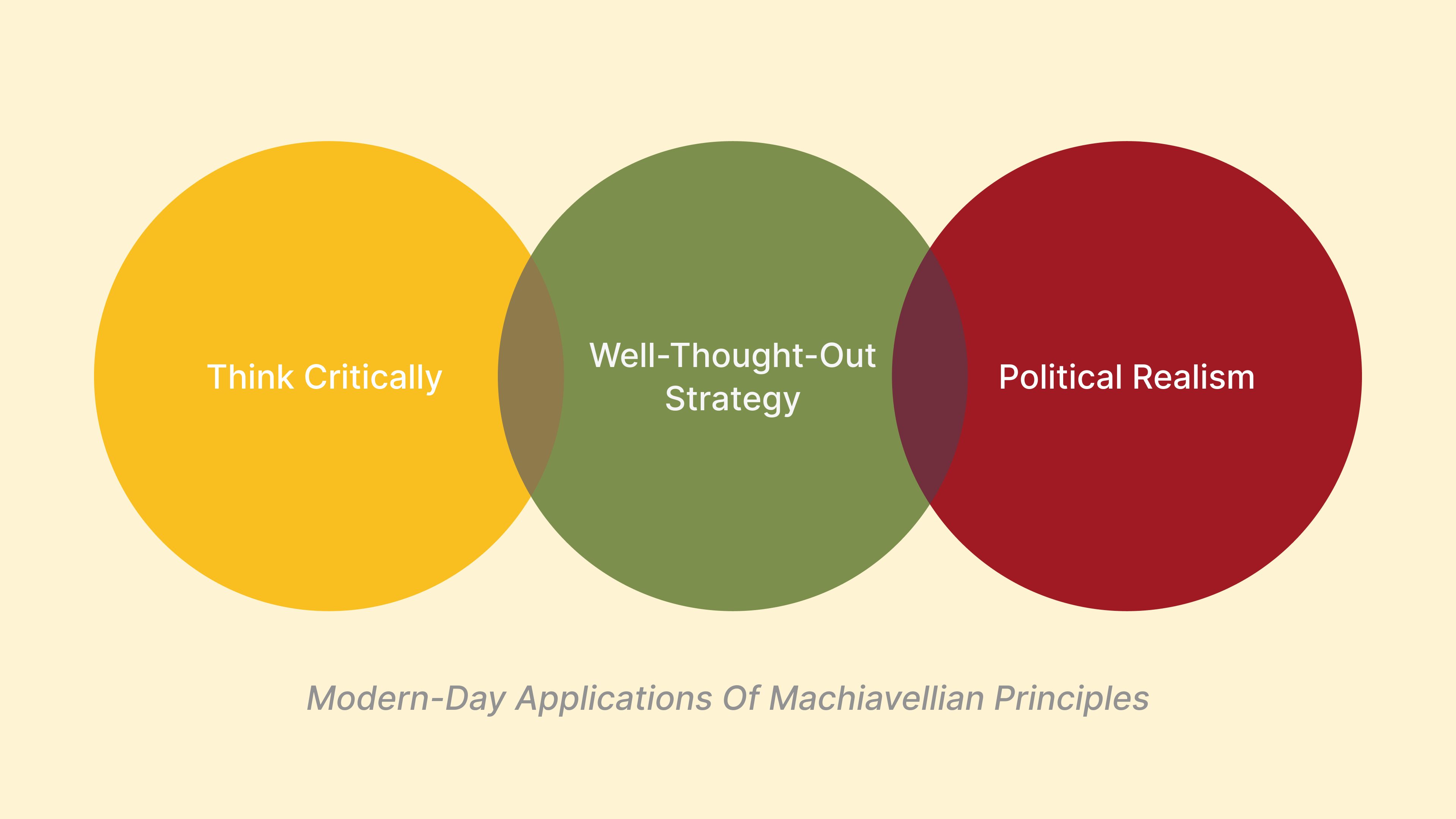

Modern-day applications of Machiavellian principles

Machiavelli takes the step of being genuinely courageous. He dares to look deep into things, opening himself up to accepting reality as it is. This allows him to peer behind the curtain of humanistic ideas hovering in the late 15th-century Italian air.

Think critically

Machiavelli's writings have often been criticized for their immorality and for claims that his pragmatism justifies any means to achieve the goal. Some have suggested that Machiavelli did not consider cruelty or dishonesty the norm but simply described the real politics of the time and gave advice on how to succeed. A realistic vision of the problem, skepticism and critical thinking, the use of manipulators' weapons as a means of protection, concealing actual ideas, and maintaining power are all relevant today.

Well-thought-out strategy

Thinkers like Baruch Spinoza, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Denis Diderot argued that Machiavelli was more of a republican and that his works inspired the democratic political philosophy of the Enlightenment.

Prominent political theory scientists of the 20th century, Leo Strauss (1899–1973) and Harvey Mansfield (b. 1932 ), criticized Machiavelli for his revolutionary thoughts. They also pointed to his subversion of religious authority and moral Christian views in favor of achieving power by any cynical means. However, Mansfield claimed that it was not cynicism but a well-thought-out strategy. Interestingly, this strategy is possible for a modern politician and leader because it is pragmatic and allows for strong power.

Political realism

German philosopher Ernst Cassirer (1946) held that Machiavelli simply adopted the

stance of a political scientist. A leader adapts to the circumstances, and politics can be separated from morality and virtue. Still, at the same time, it is essential not to forget about ethics and humanism.

As British historian Quentin Skinner, one of the founders of the Cambridge School of the History of Political Thought and author of the biography 'Machiavelli,' has shown, Machiavelli's teachings are consistently republican on both a practical and ideological level. Thanks to their diverse citizenship, republics can better adapt to rapidly changing circumstances. They also allow for participation in political affairs and military campaigns, which better ensures the fullness of their self-realization.

The life that forged the philosopher

Let's explore Niccolò Machiavelliʼ life in more detail.

Childhood

Machiavelli was born on May 3, 1469, in the family palace on Via Romana in Florence. His father was the renowned lawyer Bernardo Machiavelli, and he grew up in the "golden age" of Florence under the regime of Lorenzo de' Medici. His family spanned several generations and gave Florentine politics many famous figures. However, by the time Niccolò was born, his family had become impoverished and small, and he noted that he spent his childhood in poverty and hardship.

Although Niccolò Machiavelli never studied at the university, his father collected an extensive library, which helped Niccolò learn about philosophy. He did not know the common Greek language but was fluent in Latin. This did not prevent him from receiving an excellent education based on the works of ancient authors, such as Plato and Aristotle, which he read in their original forms.

The start of a young career

After the Medici expulsion in 1494, Florence restored its republican constitution, leading to a heated national debate on its development. Girolamo Savonarola, a reform-minded preacher, emerged as the leader of the democratic movement, aiming to create an exemplary Christian state. He believed that moral and religious purification was essential for political reform. Under his guidance, the Great Council and the Council of Eighty were established, with his protege Niccolò Machiavelli involved.

At 29, he was elected secretary of the second chancery of Florence, in charge of the republic's military and diplomatic affairs. After 1502, he reproached the new permanent head of state, Piero Soderini, the gonfalonier (chief magistrate). During his time as second chancellor, Machiavelli persuaded Soderini to reduce reliance on mercenaries by creating a militia in 1505.

From a personal point of view, Machiavelli married Marietta di Luigi Corsini when was 33, and they had five children.

European diplomat

Machiavelli was a diplomat. During his tenure, he carried out 23 diplomatic missions. He also undertook diplomatic and military missions to the court of France, Cesare Borgia, Pope Julius II, Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I, and Pisa in 1509 and 1511.

For 14 years, the thinker carried out various government assignments: with embassy members, he traveled to Italian states, the Holy Roman Empire, France, and Germany, prepared reports and certificates on current political issues, and was responsible for correspondence. However, such work and experience in diplomatic and civil service became the basis for the further creation of political philosophy and social concepts.

Unlike France and England, no force would form a national monarchy in fragmented Italy. The country fell into the sphere of interest of France and Spain, both at war. At this time and under such circumstances, the teachings of Machiavelli (1469 - 1527) arose.

Exile for bold views

When the Medici family came to power in 1512, Machiavelli resigned due to differences of opinion and disputes. An ardent Republican, he was expelled from the city for a year.

A year later, the thinker was arrested as a possible participant in the conspiracy and tortured. For some time, he still tried through intermediaries to rehabilitate himself in the eyes of the then Republic of Florence ruler, Giulio de' Medici, and his older brother Giovanni. He even dedicated his famous work 'The Prince' to the youngest Medici brothers but without success.

In August 1512, after a series of complicated battles, treaties, and alliances, the Medici, with the help of Pope Julius II, regained power in Florence and abolished the republic.

Machiavelli, who had played a significant role in the Republican government, fell into disgrace. In 1513, he was accused of conspiracy and arrested. Despite everything, he denied any involvement and was eventually released.

He retired to his estate at Sant'Andrea in Percussini near Florence and began writing treatises that secured him a place in the history of political philosophy. He lived in that estate until his death in 1527 and was buried at the Church of Santa Croce in Florence.

Machiavelli legacy

At Sant'Andrea's estate, Machiavelli had the most fruitful period of his creativity. In 1513, he wrote the work immortalizing his name in world history: 'The Prince.' He touched on the issues of unifying fragmented Italy into one strong state. In 1559, the Vatican Commission included Niccolo Machiavelli's works in the first Index of Prohibited Books.

Machiavelli was also the author of the short stories 'Belfagor-archidiavolo,' 'Life of Castruccio Castracani of Lucca,' Discourses on Livy' (Discourses on the First Ten Books of Titus Livy, Discorsi sopra la prima deca di Tito Livio), as well as the comedies 'Andrea,' 'Clizia,' and 'Mandragora.' Machiavelli wrote all three comedies between 1513 and 1520. The comedy 'Mandragora' is one of the best works of Italian comedy. Its plot comes from Boccaccio's short stories, but the development is entirely different. The optimism of the Renaissance was replaced by a sense of sad irony, making social satire more prominent. The play was revived in the 20th century and staged in New York and London theaters.

Machiavelli's political legacy also includes the 'Arte della Guerra' ('The Art of War,' 1521) and various works on political topics, including 'Discursus' (1520), reports on diplomatic missions, letters, and 'Florentine Histories' (at the request of Pope Clement VII and published 1532).

Сollaboration with Leonardo da Vinci

Machiavelli thought in an unusual and revolutionary way during his time, and he even collaborated with Leonardo da Vinci on a somewhat risky water supply plan that was gigantic by the standards of the time. They wanted to turn Florence into a port city by changing the river's course. They also wanted to use the river as a weapon against neighboring Pisa — to bring their enemy to its knees with the help of thirst.

On a completely different scale was the impudent and meticulous operation of Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), military engineer Cesare Borgia, and Florentine Secretary of State Niccolò Machiavelli. Their meeting in 1502 was one of the most fateful and mysterious events in the intellectual history of Florence and Europe.

Learn timeless and time-tested ideas with the Headway app

Machiavelli feels like a contemporary thinker, and 'The Prince' remains a fundamental guide for political strategists. If you are interested in politics and philosophy, why not read or listen to the book summary available on the Headway app? We have a library of summaries related to these topics, helping you learn and develop on-the-go.

Additionally, if you're looking for more books like 'The Prince,' visit our collections on diplomacy, strategy, and power. After all, you have only met Machiavelli and his Prince in this article, but the book summary provides a deeper dive. Download the Headway app today!

FAQ

What is Machiavelli's theory?

According to Machiavelli's theory, the state was not created by God but by people based on the need for the common good. The ruler could use deception, cunning, treachery, and violence to create a powerful state. According to Machiavelli, a high goal justifies the means, and real politics is incompatible with morality.

What was Machiavelli's famous quote?

"The ends justify the means."

Is Machiavelli moral or immoral?

Considering the problem of the relationship between duty and morality, Machiavelli assumed that fulfilling duty and obtaining the necessary results is moral, while failing to fulfill promises and achieving the goals set by a politician is immoral.

What is Machiavellianism today?

In the modern world, Machiavellianism can involve using psychological pressure and manipulation during negotiations, gathering information about competitors, controlling and shaping public opinion through the media, skepticism and critical thinking, and hiding true ideas and holding power.

What religion was Machiavelli?

Niccolo Machiavelli nominally belonged to the Catholic Church, but his writings were secular.